The maison aux symboles

Our house in Camon is known locally as the “maison aux symboles” (the house of symbols) on account of the symbolic stone carvings set into the facade. Camon has several notable buildings: the 12th century abbaye, the maison haute (the high house directly opposite ours), the bell tower, cow shoe shed, the houses which form the walls of the bastide itself and ours, the maison aux symboles.

When we bought the house in 2006 the previous owner told me he believed that the house had been built as a refuge for pilgrims walking the way of St James to Santiago de Campostela. If the abbaye itself was unable to accommodate the pilgrims they could overnight in our house, he told me. Another knowledgeable ex-Camon resident (well, so she told me anyway) assured me that the house had been a convent and that the walled garden behind, which belongs to our delightful neighbour, was in fact the kitchen garden tended by the nuns and that as such it should now belong to us. Emilie V, the youthful and dynamic face of Camon's office de tourism, related a different history for the house which, she assured me, was gleaned from village records. Emilie's “official” version is now immortalised on a plaque beside the rose on the right hand side of the door and is earnestly read by the many tourists who gaze up at the stones and take photographs.

It appears that history is indeed written by the victors and those with the power of speech. I wonder if any of the tourists who gaze at the facade of our house question the published version of the meaning of the symbols as explained on the plaque. I know I have peered closely at the symbols and carved initials and wondered if there are alternative explanations. A Léran resident with an interest in Cabal questioned the Christian nature of the inscriptions, especially the barely visible slightly Arabic-looking script in the upper triangle. Another friend who is a high-ranking mason suggested the triangle could in fact be a pyramid (the “all seeing eye”) and its position at the top of the facade could reference the supreme architect of the universe, the master builder himself. I find it fascinating that the sixteenth-century symbols which were probably intended to clearly communicate the function of the building to a largely illiterate population could be so shrouded in mystery and open to different interpretations several centuries later.

The equilateral triangle: does it symbolise the holy trinity?

In some ways I am grateful for the presence of the plaque as it means I do not have to relay the possible significance of the stones to tourists myself. On one memorable occasion I was leaning far out of our bedroom window to fasten back the shutters (clad only in a skimpy nightie) and was hailed by a group of German tourists who politely enquired as to the meaning of the stones. I felt obliged to trot out the official interpretation complete with gestures to the relevant stone. This strange looking pantomime was recorded by a particularly enthusiastic tourist who, rather incredibly, managed to hold a small white dog and film my explanation at the same time. I must check You Tube to see if this edifying piece of footage is there.

Our bedroom shutters are visible on either side of the sacré coeur stone.

*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*

So to finish here is a translation of the plaque:

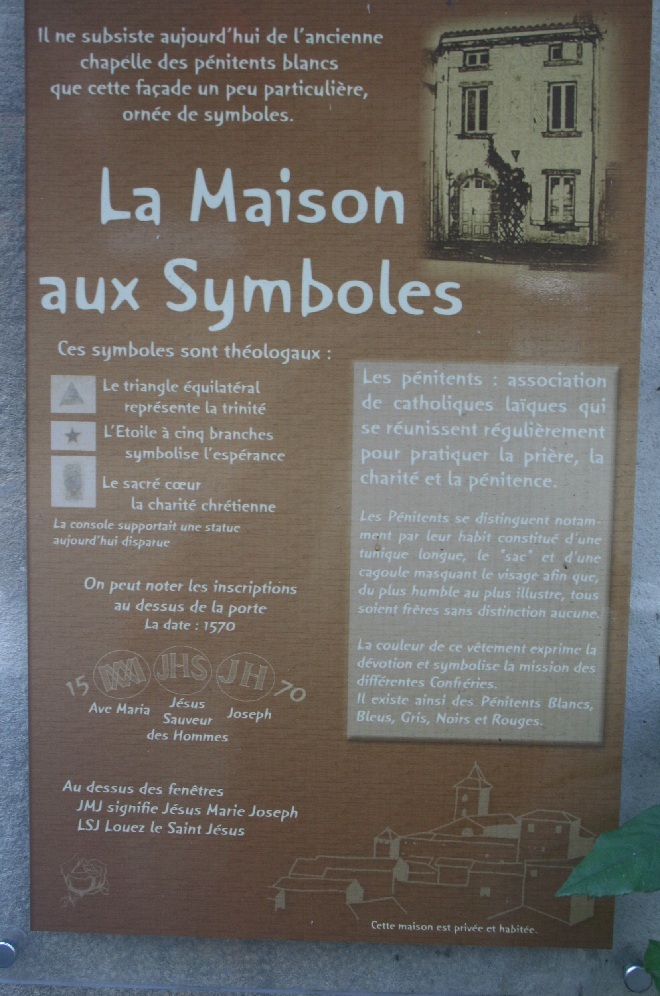

The peculiar facade which is decorated with symbols is all that remains today of the old chapel of the white Penitent monks.

The house of symbols.

These symbols are religious.

The equilateral triangle represents the Holy trinity.

The five-branched star symbolises hope.

The sacré coeur is the symbol of Christian devotion.

The plinth held a statue which has disappeared today.

One can see inscriptions above the door.

The date 1570.

Ave Maria.

Jesus, saviour of man.

Joseph.

Above the windows:

JMJ signifies Jesus, Mary and Joseph.

LSJ – praise to St. Jesus.

The Penitents: a Catholic lay association who met regularly to pray, perform charitable acts and to repent.

The Penitents were identifiable by their habit which consisted of a long tunic, a “sack cloth” and a cowl which covered the face so that the most humble member of the brotherhood could not be distinguished from the most illustrious.

The colour of the monks' habit expressed their devotion and symbolised the mission of the different brotherhoods.

The Penitents' habits existed in white, blue, grey, black and red.

*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*

What do you think?